The Netherlands, Brazil, The USA and Uruguay, Toby Upson finds a romantic self alive amongst four Pavilions in the 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia (the Venice Biennale)

‘When I Sonia you say Boyce’

“Sonia!”

“BOYCE!”

“Sonia!”

“BOYCE!”

“Sonia!”

“BOYCE!”

“Sonia!”

“BOYCE!”

Electric flash, blue; crash and crash and thud. The base kicks, drops, and rises, pushing bodies into a flow. And together, we shuffle with cackling smiles.

I always say the Venice Biennale is lads on tour. Case in point, my hazy memory-come-epigraph of the British Pavilion’s party this year. Situated in an open-air courtyard, in the centre of historic Venice, few details separate this celebration from those that unfold in the clubs of other European islands (in my mind anyway). In Venice, the floors are filled with a strange mix of people: jet-set writhe with jet proletariat. It's glorious. And for an overly enthusiastic (and I must say privileged) someone, like myself, it is an opportunity to enjoy some level of other-humanly reality. To be all neo-romantic about it, I find a self alive in the flash, blue; crash and crash and thud of the Biennale; on this city-island where rot and marble rock in a melee; where art and life truly merge for those able to access this megamix of fine finger food, fizz, and of course art!

This neo-romantic re-envisioning of humanly possibilities lies at the core of this year’s Biennale. Titled, The Milk of Dreams - a short line corralled from Leonora Carrington - many of the works in and around the Biennale seem to take a Surrealist sojourn through understandings of humanity, and indeed, understandings of being. Rather than deploying otherworldly stylistics to re-envision a dissociated world “through the prism of imagination” - to quote the Biennale’s curator Cecilia Alemani - the works that took me outside of myself each looked over, above and beyond the realities of being, helping me to grasp “new modes of coexisting” and the “infinite new possibilities of transformation” allowed for when one dreams in milk instead of pure fantasy. And so, as I await my ooh six twenty flight, it seems fitting that this tactile “re-enchantment of the world” happens when bodies take flight, arrive, move together - shuffle with cackling smiles.

With 213 artists, 80 National Pavilions, and numerous events throughout the city, the Biennale, as always, is BIG. I am not going to map this scene, nor round up what unfolded in my Venetian scuttling. Instead, by way of a constellation, here are four Pavilion encounters, of varying lengths, that pushed my alive self into joyful free flow.

melanie bonajo, When the body says Yes (Dutch Pavilion)

“Embrace your inner sloth,” melaine bonajo. I recline, falling into a soft landscape of neoprene hills and velvet foliage. Just beyond my toes, a sequined meadow and fur valley. Gazing up, I drink in the night sky rendered on the ceiling of the 10th-century Chiesetta della Misericordia Cannaregio and as my eyes drift down, they come to rest on an expansive screen suspended on the horizon. Here, slathered in olive oil, a group of naked bodies slip and slide on and over each other, jiggling with pleasure. Cut to a spring-time forest, they play wild, hanging off trees, jumping in pools. Layard over these humorous caresses, voices speak in turn about intimate moments of genital encounter and wider sexual becoming; often problematic for queer bodies in societies that have rigid notions of sexual being.

|

Exhibition view of When the body says Yes, melanie bonajo, 2022. Dutch entry Venice Biennale as commissioned by the Mondriaan Fund. Photo: Peter Tijhuis. |

Building from bonajo’s ongoing research into the possibilities for intimacy in an increasingly alienating world, the film installation is centred around one central claim: “touch can be a powerful remedy for the modern epidemic of loneliness.” With their wiggling together, the group of bare protagonists seem to be anything but isolated. That is a crass statement. Taking a holistic view of sexual bodies, bonajo’s film, and the viewing space designed by Théo Demans, hold experiential reality and somatic promise in restive tension. Not dwelling in the numbed mind-body connections that result from a commodity-driven becoming, the visual and sculptural play space of the Pavilion proposes that consensual touch can allow a body a more capacious existence. That is, in this abundant space “we discover our bodies beyond the norm,” to quote the film. And indeed, we are encouraged to register ways of holding ourselves outside of the hard pillars of western self-hood.

Jonathas de Andrede, With the heart coming out of the mouth (Pavilion of Brazil)

Through the left ear, I step inside the architectural head of this year’s Pavilion of Brazil, and a furnace of ambient noise situates me within something structural. Not so much a body in space, but a space from the body, here I hear, listening with my eyes, phrases corralled from day to day Brazilian life. These fragments - where the body acts as a metaphorical vessel for communication - are so much more than poppy figures of speech; they pertain to tongues in ears, that is to the divisive spectacle of rhetoric.

|

Exhibition view of With the heart coming out of the mouth at the 2022 Brazilian Pavilion. Courtesy Ding Musa / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

|

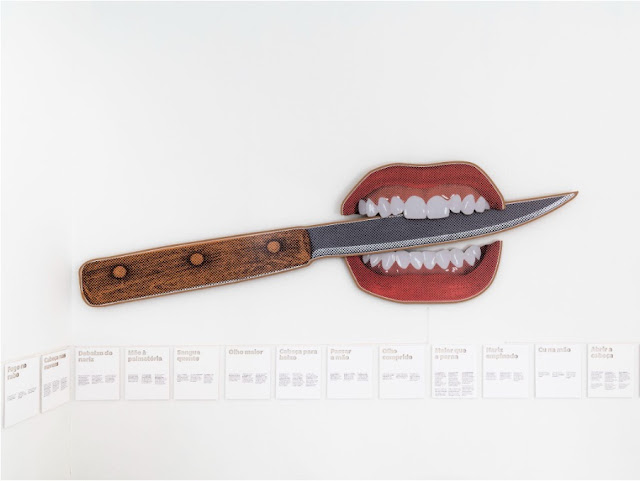

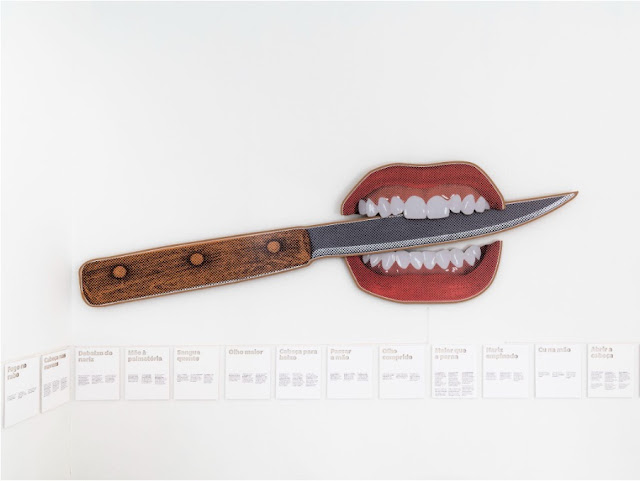

For Jonathas de Andrede the idiosyncrasies of the Brazilian people are a point of interest. In particular, how quotidian peculiarities can express something of the social, political and economic obfuscation many Brazilians face. For his work in this year's Biennale, the artist gives common phrases a mass-culture visuality: “faca nos dentes” (“knife in the teeth”) here rendered sassy; large red lips surround bare teeth and holding a blade at a rakish angle. With their journalistic grain, the pixelated pores of these cardboard wall-works recall the way in which narratives can infect our minds. It is fitting therefore that these spores fill the two lobes of the Pavilion of Brazil’s head.

|

Exhibition view of With the heart coming out of the mouth at the 2022 Brazilian Pavilion. Courtesy Ding Musa / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo. |

|

Exhibition view of With the heart coming out of the mouth at the 2022 Brazilian Pavilion. Courtesy Ding Musa / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

|

Moving from the left to the right side of the Pavilion, the abounding sound that gripped me upon my entry becomes one of the points of focus. Like the isolated snippets of visual metaphor, the video Nó na garganta [Knot in the Throat] brings together scenes of human and non-human comportment; hands curl, feet twitch, snakes become one with bodies, monkeys, leaves appear, and fires burn. Pairing the seemingly mundane with the horrific, or thrilling, the 38-minute filmatic collage is displayed on a large, pixelated screen - the kind you might expect to see at a political rally - and is accompanied by a soundtrack that pumps a vital energy into the Pavilion space. Not a clack, pulse, nor symmetrical rhythm, this aural is a fizzle; it is its own kind of syncopated jitter, messing up the logic of the oppressive narrative.

As I witness the video unfurl, a gentle pushing on my back forces me to a wall and mares my abilities to move, see, and be an active body in this rhetorical space. The large kinetic sculpture com o coração saindo pela boca [with the heart coming out of the mouth], comprises of a pair of lavish lips and a huge red tongue that inflates filling the right side of the Pavilion. Perhaps an overt reference to the ways in which speech can and does divide bodies, this work, as with the others in the Pavilion, makes clear how the body can transcend its corporeality, becoming a communicative device, one that has the ability to bridge as well as to barricade.

|

Exhibition view of With the heart coming out of the mouth at the 2022 Brazilian Pavilion. Courtesy Ding Musa / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

|

Simone Leigh, Sovereignty (U.S. Pavilion)

Ooohsh! It was the first sound I made upon entering the Arsenale. A day later; awwwwe! a similar reaction upon walking into the U.S. Pavilion and witnessing the beautiful monuments cast by Simone Leigh. As an incessant follower - lover - of Tina M. Campt’s writing and precise mode of giving form to theory, I have read many gorgeous descriptions of Leigh’s work. Experiencing her anthropomorphic female figures in person, I am left, suspended, left breathless.

|

Simone Leigh, Last Garment, 2022. Bronze, 54 × 58 × 27 inches (137.2 × 147.3 × 68.6 cm). Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo by Timothy Schenck. © Simone Leigh.

|

A blackened pool hollows the first room of the U.S. Pavilion. Its utter tranquillity does not so much holds but push me to a perimeter, where I teeter, on harrow edge, one step away from feeling weighty sublimity. Last Garment, is a seemingly simple bronze figure of a Jamaican woman washing her clothes. No patina, no fuss, just a woman doing her thing to care, to survive. I am transfixed. Caught up in the bouquet of knots that form the figure's hair; taken aback by the majesty of the way in which her form curls, as a crane, exhaling, and in turn exuding nothing but powerful atmospherics. Stillness. Quiet. In a word, Leigh's figure epitomises her own sovereignty; described in the Pavilion’s guide as “not [being] subject to another’s authority, another’s desires, or another's gaze, but rather to be the author of one’s own history.”

Originally pictured on a colonial-era postcard, the figure Leigh has based Last Garment on was meant in its own time (the 1870s) to establish the idea of Jamaica as a “tropical Paradise” and Jamaican people as “loyal, disciplined, and clean” - to re-quote Krista Thompson from the guide. These associations aimed to make Jamaica an attractive destination for British colonists who were embracing the burgeoning tourist industry. The original postcard, photographed by C.H. Graves, debased its sitter of all self-determined agency. Looking at a reproduction of this souvenir in the Pavilion’s guide, what jumps out to me is the way in which the figure of the woman washing her clothing seems to be penned in; she is trapped in a gushing stream by a steep bank and wire fence. It is almost as if this woman is a zoo animal, held in a cage for our gaze, desire, and the delight we find in the otherly.

Leigh’s bronze counters this narrative. Recasting the washerwoman figure in fine detail, with an elegance, and a sense of self-determined strength. Despite the colonial atmosphere, in Graves’ original image, the face of the figure seems at peace; eyes cast down, exhaling, with a sense of dignity being excluded in the small details of this woman’s decorum. Accentuating these aspects of the image, Leigh’s figure, a figure trapped in its own pool, refuses to capitulate to a regime where she is a fetishised object, only finding validity as she circulates through the vernacular tourist trade. With her face cast down, her delicate hold, and the stillness of her pool, the figure in Last Garment demands we register and engage her as a sovereign self, whilst also paying feeling in some way culpable to the history this woman is bringing out in the wash.

Gerardo Goldwasser, Persona (Uruguay Pavilion)

A white cube and a man-sized mirror; the language of modernity is pretty copy and paste. Delving into and beyond the cuts that form the ‘uniform(is)ation’ of a being in society, Gerardo Goldwasser’s project for the Uruguay Pavilion, Persona, is labelled as an opportunity for critical reflection. The elegant sculptural intervention consists of 18 reels of charcoal black felt, 50 cloth sleeves, a rigid measuring stick and that large mirror. Drawn to both the minimal black and white aesthetic of the exhibition as well as its conceptual becoming, I find Persona one of the most accomplished Pavilions, indeed works, in this year's Biennale.

Using the fashion industry as a cypher for human becomings, Goldwasser’s conceptual critique weaves together numerous historical threads - Venice as a city of fashion (particularly the operatic possibilities of fashion), Uruguay as a colonial stopover-come-refuge for political émigrés, and his own Jewish history - to unravel tensions held innate to modernity and its bio-political proteges.

|

Gerardo Goldwasser, Mesa de corte, 2022. 18 reels of black cloth, 270 × 540 × 330 cm. Photo: Rafael Lejtreger. |

Bundled in three pyramids of six, the 18 reels of inch thick black felt that compose Mesa de corte [The Cutting Table] are monolithic. Almost filling Uruguay’s small pavilion space, the softness of the fabric transforms from something holding - of comfort, warmth - into something dominating - restrictive and stark. As with any monument, sitting with these tombs, listening to how the materials whisper to us - to paraphrase Pablo da Silveira in the catalogue - a complex history of discipline and disguise emerges. As I move around the Pavilion’s space, one of the secrets sequestered behind Mesa de corte's initial exterior comes into view: hundreds of tailors' cutting patterns cling to one side of the dark felt rolls. These misty white panels, templates for things to become, accentuate the grain of their woollen base, weeping pale blue-green tears in anticipation of the standardised life they are to enter into.

|

Gerardo Goldwasser, Mesa de corte, 2022. 18 reels of black cloth, 270 × 540 × 330 cm. Photo: Rafael Lejtreger. |

Taken from a book of tailors patterns, inherited from his grandfather, Goldwasser’s use of template pattern pieces alludes to the ways in which industry sets itself up to eliminate difference; to “sustain a rigid pre-established order with the purpose of producing uniformity,” as Laura Malosetti Costa and Pablo Uribe state. Following this logic of industrial re-production, the material forms in Persona draw a line between capitalist standardisation and modes of authoritarian rule. (It is of note that the book of standardised patterns used in Mesa de corte were, perhaps, originally templates for Nazi military uniforms. As a Jewish tailor, Goldwasser’s grandfather survived his imprisonment in the Buchenwald death camp because of his professional skills.)

Gerardo Goldwasser, El saludo (detail), 2010-2022. 85 black fabric sleeves pinned to the wall. Dimensions variable. Photo: Rafael Lejtreger.

El saludo [The Salute], a line-up of sum 50 left arm suit sleeves pinned to one wall of the Pavilion, parades like a well-groomed regiment before Mesa de corte. The juxtaposition of these two works further the connection between authoritarian modes of governance and the ways in which we present our bodies to conform to some kind of social geometry. In their poetic whispers, however, this delicate line-up of vilified lefts seem to call out together, positioning us as witnesses to the bio-political standardisation of both bodies and minds innate to hegemonic modes of social re-production.

With its title, El saludo references an encounter; a moment of appearance upon which one faces an other making some kind of judgement. Leaving the Uruguay Pavilion, I turn and face the man-sized mirror, a work titled Medidas directas [Direct Measurements], situated at the entrance to the Pavilion. Gazing at my tired suit and unkempt face, my thoughts turn to the various personas I have and do don, especially whilst on the other-humanly floors of Venice.

Despite the elitism of Venice and the wider art world, my encounterings at this year's Biennale have returned to me some of the naive promise I have in art. A hope perhaps best surmised by Cecilia Alemani when she gave shared her thoughts on the role of the Biennale following the covid-19 pandemic; she states, “the simplest, most sincere answer I could find is that the Biennale sums up all the things we have so sorely missed in the last two years: the freedom to meet people from all over the world, the possibility of travel, the joy of spending time together, the practice of difference, translation, incomprehension, and communion.” Personally, I feel joy and possibility, togetherness and difference, incomprehension and communion are key sensorial assets to any notion of being or becoming in this world. If it takes lads on tour to glimmer these innately human characteristics count me in.

Toby Upson

The 59th Biennale di Venezia runs from 23 April to 27 November 2022