The big summer exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum covers a lot of bases but fails to delve below the surface glitz. Cathy Lomax basks in the glow of the glamour

|

| Marilyn Monroe projected on the ceiling of the Victoria and Albert Museum above the DIVA exhibition |

DIVA begins (naturally) with ‘Act One’ in which the scene is set by two white marble portrait busts of Juno and nineteenth century opera star Adelina Patti. This poetic start neatly leads us to French writer and critic Théophile Gautier who first described the female opera singer as a diva (the Latin word for goddess) as he considered her talent to have been divinely bestowed. Although today's diva still has the heavenly looks the term has expanded and now denotes a flamboyant performer who is also what we might call a prima donna.

|

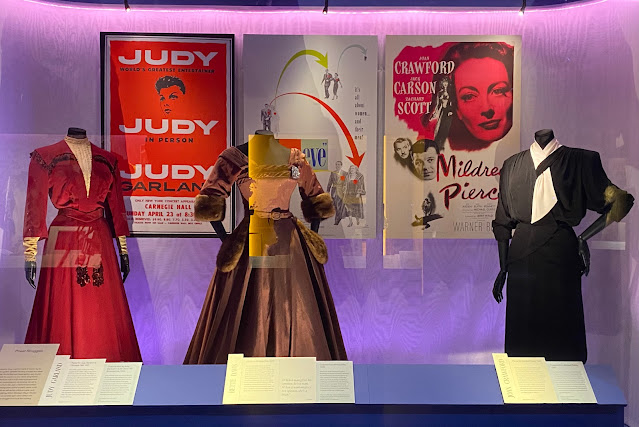

| Hollywood costumes as worn by Judy Garland, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford |

I think I first became aware of the term when the film Diva (1981) was released and as I understood it, it described a highly strung, temperamental opera singer. In the DIVA exhibition opera swiftly gives way to theatre with Sarah Bernhardt and Ellen Terry effectively trailing my favourite section – Hollywood stars. There is some pure gold here with representation from the early days of cinema through to Elizabeth Taylor’s turn in Cleopatra in the 1960s. The film costumes on display are quite spectacular in terms of their importance to film history with this classical Hollywood fan practically swooning at Joan Crawford's Mildred Pierce dress, Bette Davis' satiny All About Eve ensemble and Marilyn Monroe's little black Some Like it Hot dress (other costumes on display include those worn by Clara Bow, Josephine Baker, Theda Bara, Mary Pickford, Carole Lombard, Judy Garland, Vivien Leigh and Mae West). Many of the costumes are brought to life by photographs and well selected film clips. Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra commanding Richard Burton’s Marc Anthony to kneel before her is perfect high camp! Beyond the visual delights the complicated tussle between the exploitation and agency of stars (and women in Hollywood more generally) is suggested in accompanying texts but this is never quite explored thoroughly or argued convincingly.

|

| Cleopatra (1962) |

A note here about the audio guide which rather than the usual dull and user-unfriendly offering was cleverly broadcast from a set of headphones that sit above the ears and respond automatically to exhibits providing musical and film sound accompaniment rather than wordy (often tedious) explanations. This soundtrack propelled me through the exhibition and helped to smooth over some of the more clunkily and tenuous inclusions of the chosen cast of mostly female stars.

|

| Bob Mackie talks Cher |

Upstairs in ‘Act Two’ the emphasis is on ‘the diva today’ and it is musical stars (of all genders) that dominate. Alongside Beyonce, Rihanna and Lady Gaga, there is a stunning centrepiece featuring some of Cher’s figure-hugging bespangled outfits designed by Bob Mackie. It was only after circling the exhibit that I realised that the dapper elderly gentleman being interviewed was Mr Mackie himself!

|

| The austere Edith Piaff exhibit |

I am not any clearer about what exactly it is that the exhibition defines as a diva – profiles of performers as disparate as Nina Simone, Siouxsie Sioux, Edith Piaff, Elton John, Sade, Ella Fitzgerald, Janelle Monáe, Prince, Kate Bush and PJ Harvey are closely clustered together. Is a diva a show off? Or maybe a successful entertainer who likes dressing up? The press release describes the ‘Act Two’ divas as reclaiming the title and using it as ‘an expression of their art, voice, and sense of self’. But surely Billie Holliday and Ella Fitzgerald made a living singing and their emphasis was on music rather than image. I suspect the pull will be the contemporary ‘divas’ with their Met Gala outfits who in effect operate as successful business people rather than artists per se. Rihanna, we are told, is the wealthiest female musician in the world with her $1.7 billion fortune mainly built through her 'suite of companies'. But there are efforts to link these contemporary divas with their Hollywood counterparts. Such as a 2017 sketch of Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty makeup which recalls a caption describing Mary Pickford’s makeup line of the 1930s which is displayed alongside her makeup case in Act One. And of course Elizabeth Taylor demanded and received a $1 million dollar fee to play Cleopatra, which made her the highest earning performer in Hollywood history. So maybe little has changed!

|

| Sketches for Rihanna's Fenty Beauty makeup, 2017 |

|

| Mary Pickford's makeup case, circa 1938 |

There is a lot to enjoy here but it is only a very brief introduction to the style and careers of the very many talented people represented. Maybe more of a focus on a particular era, or a reduced list of featured artists, would have made for a better exhibition? As it is the diva premise feels a little woolly (film director Lois Weber may have been a female pioneer in early Hollywood but not sure why she is a diva) and this is really a mere introduction to these magnificent performers with extra work from the viewer essential to fill in the details of their dazzling and fascinating careers.

Cathy Lomax

June 2023

DIVA

Victoria and Albert Museum

London

24 June 2023 – 24 June 2023